(I discuss the novel, but I have avoided spoilers as best as I can.)

George Eliot’s Middlemarch regularly ranks as one of the greatest Victorian, greatest British, greatest English-language, or just plain greatest novels of all time. It seems to fare better on critic lists than reader lists, but if it’s a list of 100, Middlemarch is usually on there. The first time I took special notice of it was about fifteen years ago when I saw this quote: “He distrusted her affection; and what loneliness is more lonely than distrust?” I remember making a mental note that maybe one day I should read the book that this perceptive little line came from. Once the book was on my radar, I started to see it pop up regularly and became even more inclined to read it… eventually.

About two years ago, in one of those ambitious moments where I forget that I already own dozens of books I have never read (and also work at a library), I purchased a copy of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Middlemarch. I put it on my bookshelf with the rest of my unread books, and let it sit there, nagging me like the others. Sometimes I would get up in the middle of the night to get a glass of water and pass its massive glowing white spine in the darkness. “I’ll read that eventually,” I would think to myself sleepily and thirstily.

In March, when a majority of the planet shutdown because of the “novel coronavirus” (pun intended!), I decided to finally read it. After all, if I didn’t read it when I was more or less trapped inside for a month or two, when would I ever?

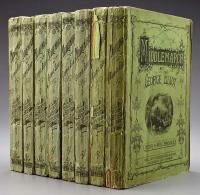

And so, in the middle of March, I began to read Middlemarch. The book takes place between 1829 and 1832 in a fictitious town in central England, and is primarily about Dorothea Brooke, a very intelligent and beautiful young woman, and the role she comes to play in the lives of many of the other townspeople. It’s divided into eight volumes that are about one-hundred pages each, so my goal was to read at least one volume per week and finish it by mid-May. The first week went swimmingly, and I finished volume one pretty quickly. I found the characters interesting and the plot engrossing. It was a little dull, but I was ready for that. There were lots of admirable turns of phrase to make the aspiring novelist in me jealous. The narration was regularly insightful and the author clearly had a sense of humor about things, even if it was very stiff and English. It was like the “homework” version of authors I really like, like Dickens or Charlotte Bronte, but I was going to be able to do this!

Then somewhere around end of volume two, I think, a whole bunch of new characters were introduced and the scope of the novel widened quite a bit. I got a little lost, and made it much harder on myself by putting the book down for almost two full weeks while I worked on a different project. Once again, the book just sat there on my desk or on my coffee table nagging me. But I wasn’t going to give up. I was determined. I’ve started way too many books and abandoned them a quarter of the way in - even when I like them - simply because I distract easily, but I wasn’t going to let that happen to me this time.

By late April, I was pretty much back in action. I regularly fell a little short of my reading goals, but usually I was making good weekly progress. I continued to miss the focus on Dorothea from the first volume, but I was starting to understand who most of the other characters were and was warming up to them as well.

I felt for Fred Vincy, an immature goofball who had no real professional goals, but only the personal goal to wed Mary Garth. I liked all the Garths for being seemingly perfect people with morals as sturdy as stone and an equally, delightfully hard indifference toward social winds and considerations. As great as every scene with Caleb Garth was, the scene with Mary and the ailing Featherstone was the highlight of the book for me. After finding out about his scandalous Continental past, I was very curious to see what Dr. Lydgate was going to get up to. I loved and then pitied the beautiful and spoiled Rosamond. And although she wound up being relatively minor, I think Celia might have been my favorite character overall. In a novel with several stuffy intellectuals and idealists, she was a very welcome, lightly sardonic voice of practicality and common sense.

Still, it was not a breezy read, and at times I had to push myself to keep going. The dialogue was generally very compelling, but the narrative alternated between inspired, better-than-average, and laborious - and the novel felt like 90% narrative. Sometimes it would take me twenty minutes to read a ten-page chapter, and other times it would take me a long hour. I would often find myself re-reading a sentence a dozen times before I actually read it. Other times my eyes would keep moving down half of a page or more while my mind wandered off, and I’d realize it and have to yank the leash to bring them back into alignment and we’d all go crawling back up the page. Or, as the book says, “Unhappily her mind slipped off it for a whole hour; and at the end she found herself reading sentences twice over with an intense consciousness of many things, but not of any one thing contained in the text. This was hopeless.”

My wife sensed that I was making myself read it rather than becoming absorbed in it and loving it, but I always had to argue if she suggested that I wasn’t liking it. I was liking it a little, I insisted. Here and there, and maybe overall. Sometimes a lot! But there was so much of it, and I definitely wasn’t liking all of it. But that’s just how literature is, babe.

A friend of mine who loves the novel told me that “the last three-hundred pages fly by,” but as I entered the homestretch in early June, I did not find that to be the case. They moved by quicker than much of the middle of the book, but it was almost never a page-turner. I could do the pages and pages of characters internally parsing through the personal, social, or spiritual ramifications of some minor decision. But I truly struggled when they would go into discussions on medicine or biology, which, thankfully, was not much of the novel. There was some historical value to that, and I’m a person who defends all the non-fiction sections on whaling in Moby Dick (one of my favorite books), but some of that was too much for me. I also feel like there were some characters and places we got a few pages about and then never saw again. Obviously I’m in no position to be giving notes to George Eliot, but Mr. Rigg and Raffles kind of came out of nowhere, and with all the fuss about the hospital in the middle of the book, that sure seemed to fade away by the end.

Nevertheless, by the middle of June when I finally finished the book - nearly three months after I started it, and as the world was starting to fully open up again - I did admire how so much of it had tied together, both thematically and plot-wise. It’s a huge book, and it contains what feels like an entire living town and several fully realized people. Even though I didn’t love it all and it took a lot of work for me to finish it, I’m very glad I read it. It is full of keen examinations of very different types of people, some really beautiful writing, and it was fun to watch the plot coagulate. Sure there were some loose ends and some tedious discussions of medicine and “pickled vermin,” but I’m putting it back on my shelf feeling nourished and accomplished. And instead of nagging me, that thick white brick on my shelf will gaze down at me lovingly, inviting me back to the pleasant little town of Middlemarch and reminding me of the shutdown of 2020.

If we ever shut down again, I’m going for The Brothers Karamazov.

Since it was a great quote that first attracted me to Middlemarch, I have included below all of the quotes from the novel that I put into my “quote book.” Hopefully one of them hooks you. They should be pretty spoiler-free, but if you are very worried about that, just avoid the last one.

"…at which everybody turned away from Mr. Hackbutt, leaving him to feel the uselessness of superior gifts in Middlemarch." - Narrator (I imagine everybody who has ever felt smart has also known this feeling.)

“If you go upon arguments, they are never wanting, when a man has no constancy of mind. My father never changed, and he preached plain moral sermons without arguments, and was a good man - few better. When you get me a good man made out of arguments, I will get you a good dinner with reading you the cookery-book. That’s my opinion, and I think anybody’s stomach will bear me out.” - Mrs. Farebrother.

“He only wanted her to take more emphatic notice of him; he only wanted to be something more special in her remembrance than he could yet believe himself likely to be. He was rather impatient under that open ardent good-will, which he saw was her usual state of feeling. The remote worship of a woman throned out of their reach plays a great part in men’s lives, but in most cases the worshipper longs for some queenly recognition, some approving sign by which his soul’s sovereign may cheer him without descending from her high place. That was precisely what Will wanted. But there were plenty of contradictions in his imaginative demands.” - Narrator

After Dorothea says that art doesn’t seem to her to make the world any better… “‘I call that the fanaticism of sympathy,’ said Will, impetuously. ‘You might say the same of landscape, of poetry, of all refinement. If you carried it out you ought to be miserable in your own goodness, and turn evil that you might have no advantage over others. The best piety is to enjoy - when you can. You are doing the most then to save the earth’s character as an agreeable planet. And enjoyment radiates. It is of no use to try and take care of all the world; that is being taken care of when you feel delight - in art or in anything else. Would you turn all youth of the world into a tragic chorus, wailing and moralizing over misery? I suspect that you have some false belief in the virtues of misery, and want to make your life a martyrdom.’”

“But we all know the wag’s definition of a philanthropist: a man whose charity increases directly as the square of the distance.” - Mr. Cadwallader.

“I call it improper pride to let fools’ notions hinder you from doing a good action. There’s no sort of work that could ever be done well, if you minded what fools say. You must have it inside you that your plan is right, and that plan you must follow.” - Caleb Garth.

“Caleb was in a difficulty known to any person attempting in dark times and unassisted by miracle to reason with rustics who are in possession of an undeniable truth which they know through a hard process of feeling, and let it fall like a giant’s club on your neatly-carved argument for a social benefit which they do not feel.” - Narrator.

“Who can know how much of his most inward life is made up of the thoughts he believes other men to have about him, until that fabric of opinion is threatened with ruin?” - Narrator

“Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” - Narrator.