Seventy-five years after the civil war, the last vestiges of slavery in the United States were documented. The remains of plantations, slave quarters, cabins and barns--some long abandoned--were photographed. Thousands of formerly enslaved African American men and women provided first-hand accounts of life under slavery. Now, these words and pictures are paired to offer insight into a shameful time in American history that resonates today.

This beautifully designed book is a wonderful record of a dark part of U.S. history. The editors have carefully selected key statements and anecdotes from a variety of people who lived through slavery to weave a quilt that tells the story of the enslaved experience from many perspectives. It's top-notch, embodied history. I highly recommend it.

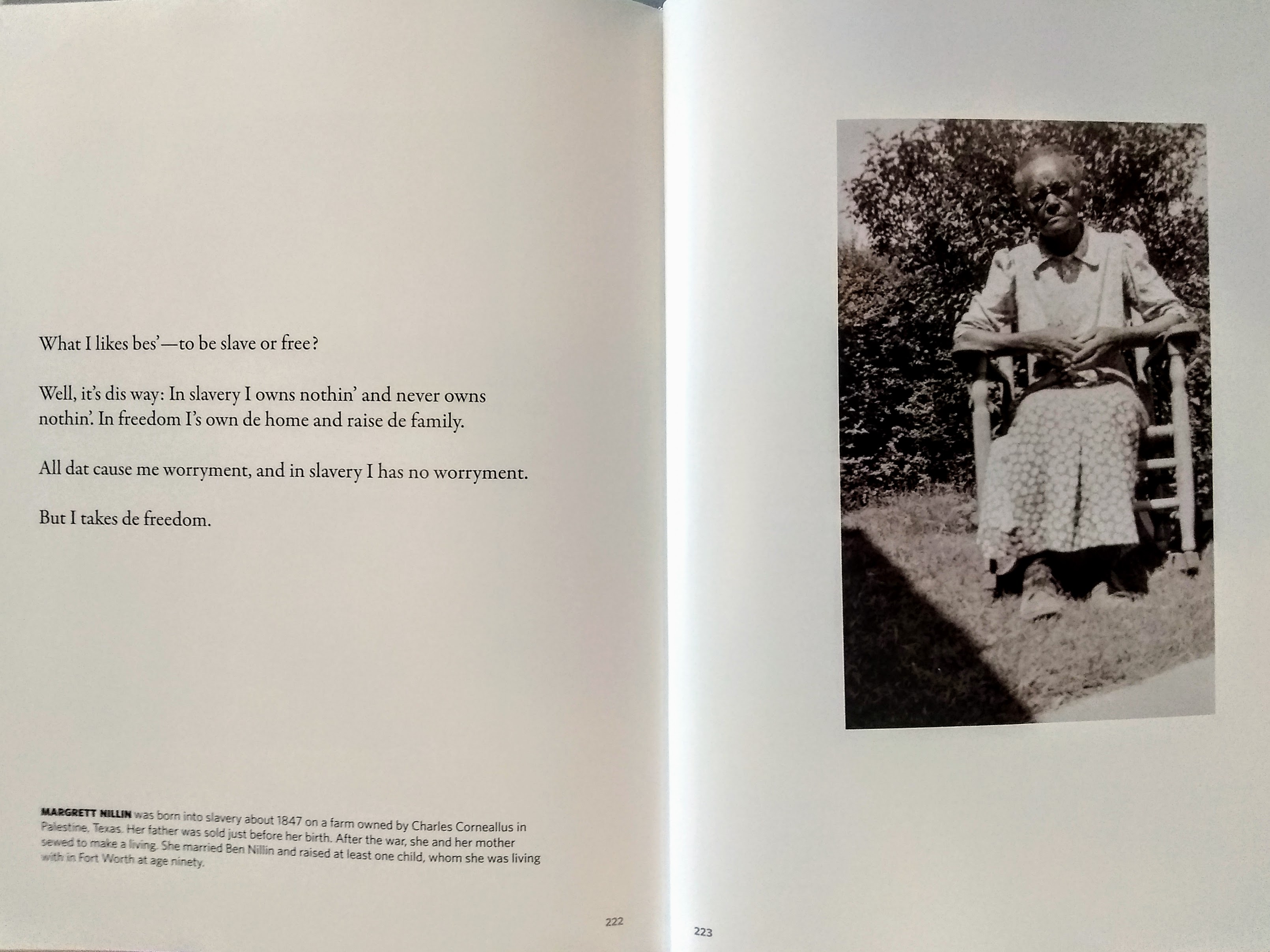

As you can see in the picture above, each spread provides a picture of the speaker, some of their words from the interview with them, and a short factual biography about their life. These spreads are thematically arranged to document U.S. slavery in a roughly chronological fashion.

I want to highlight the book here especially to recognize the source material it emerged from, the Federal Writers' Project of the 1930s. From the introduction:

The Federal Writers' Project [was] a branch of the Works Progress Administration. The WPA was a government agency set up to provide work to the one-quarter of Americans who were unemployed during the Great Depression. More than 8 million men and women were hired by the WPA to build roads, bridges, dams and parks--and to paint, sculpt and write. "Hell," said relief administrator Harry L. Hopkins, "artists have got to eat just like other people."

The WPA's Federal Writers' Project hired more than 6,500 unemployed writers, historians and teachers to gather the nation's history. They produced 48 books called The American Guide series for each state, as well as dozens of books and pamphlets of cities and regions. They also interviewed 10,000 ordinary Americans.

Federal Writers' Project managers were described as "romantic nationalists" because they were interested in the words and thoughts of almost everyone--from story clerks to prostitutes to meat packers. Everybody had something to say. The work of the government writers was a celebration of diversity and democracy.

Ten years ago, I read another book pulled from the work produced by the Federal Writers' Project: The Food of a Younger Land : A Portrait of American Food From the Lost WPA Files, edited by Mark Kurlansky. It does an equally wonderful job of capturing an aspect of U.S. history. At the time, I wrote:

I’m ashamed to admit I dropped my Kansas Folklore class in college. In some ways I think I was too young to really appreciate the topic, but in other ways I enjoyed it too much. Or I enjoyed it in the wrong way, rather. It was fascinating and fun, not academic, so I listened and read with rapt attention but never really took notes or consolidated my learning, and when it came time to take tests over facts and details I realized I was totally unprepared. To preserve my GPA, I dropped it halfway through the semester and stopped going. (But not before hearing how my professor became the foremost authority on the history of the cattle guard.)

Nevertheless, my interest in folklore has remained. Grown, if anything. Which made The Food of a Younger Land a great fit for me. This book is a portrait of the culture of the United States as seen through food practices before technology homogenized everything, when food was still local and eating had a very distinct regional personality. It’s history and anthropology and food and cooking and writing, all rolled into one package.

In some ways I could have quit after the lengthy introduction and been happy, because I learned about an aspect of U.S. history I was unaware of. A bit too much of that introduction follows, so I won’t belabor the point here, just say that it was fascinating reading. As was the rest of the book, although I approached it in the wrong way. It reminded me more than anything of travel food TV shows like Anthony Bourdain’s and Andrew Zimmern’s, where they use food to learn about cultures. Those are episodic in nature, and if you watch too many in a row you begin to lose track of anything practical you’ve learned. I listened to the audio of this book in marathon sessions and found myself too frequently losing focus on the string of essays, recipes, and whatnot, because this is best digested in bits and pieces since that’s what it’s composed of. I’d like to go back and reread much of the actual book when I get a chance. And try some of the recipes, even. Highly recommended.

Kurlansky, from the introduction:

A few years ago, while putting together Choice Cuts, an anthology of food writing, I discovered to my amazement that government bureaucrats in Washington in the late 1930s were having similar thoughts. But these were not typical bureaucrats because they worked for an agency that was unique in American history, the Works Progress Administration, or WPA. The WPA was charged with finding work for millions of unemployed Americans. It sought work in every imaginable field. For unemployed writers the WPA created the Federal Writers’ Project, which was charged with conceiving books, assigning them to huge, unwieldy teams of out-of-work and want-to-be writers around the country, and editing and publishing them.

After producing hundreds of guidebooks on America in a few hurried years, a series that met with greater success than anyone had imagined possible for such a government project, the Federal Writers’ Project administrators were faced with the daunting challenge of coming up with projects to follow their first achievements. Katherine Kellock, the writer-turned-administrator who first conceived the idea for the guidebooks, came up with the thought of a book about the varied food and eating traditions throughout America, an examination of what and how Americans ate.

She wanted the book to be enriched with local food disagreements, and it included New England arguments about the correct way to make clam chowder, southern debate on the right way to make a mint julep, and an absolute tirade against mashed potatoes from Oregon. It captured now nearly forgotten food traditions such as the southern New England May breakfast, foot washings in Alabama, Coca-Cola parties in Georgia, the chitterling strut in North Carolina, cooking for the threshers in Nebraska, a Choctaw funeral, and a Puget Sound Indian salmon feast. It also had old traditional recipes such as Rhode Island johnny cakes, New York City oyster stew, Georgia possum and taters, Kentucky wilted lettuce, Virginia Brunswick stew, Louisiana tete de veau, Florida conch, Minnesota lutefisk, Indian persimmon pudding, Utah salami of wild duck, and Arizona menudo. Ethnic food was covered, including black, Jewish, Italian, Bohemian, Basque, Chicano, Sioux, Chippewa, and Choctaw. Local oddities, such as the Automat in New York, squirrel Mulligan in Arkansas, Nebraska lamb fries or Oklahoma prairie oysters, and ten-pound Puget Sound clams, were featured. Social issues were remembered, as in the Maine chowder with only potatoes, the Washington State school lunch program, and the western Depression cake. There was also humor to such pieces, as the description of literary teas in New York, the poem "Nebraskans Eat the Weiners," and the essay on trendy food in Los Angeles.

Kellock called the project America Eats. . . .

Ironically, the chaotic pile of imperfect manuscripts has left us with a better record than would the nameless, cleaned-up, smooth-reading final book that Lyle Saxon was to have turned in. A more polished version would still be an interesting book today, a record of how Americans ate and what their social gatherings were like in the early 1940s. Like the guidebooks, it would have been well written and well laid out. And it would not have had frustrating holes and omissions. But we would have had little information on the original authors. There are among these boxes a few acknowledged masters, such as Algren and Eudora Welty, some forgotten literary stars of the 1930s, and authors of mysteries, thrillers, Westerns, children’s books, and food books, as well as a few notable local historians, several noted anthropologists, a few important regional writers, playwrights, an actress, a political speechwriter, a biographer, newspaper journalists, a sportswriter, university professors and deans, and a few poets. They were white and black, Jews, Italians, and Chicanos--the sons and daughters of immigrants, descendants of Pilgrims, and of American Indians. Typical of the times, there were a few Communists, a lot of Democrats, and at least two Republicans.

One thing that shines through the mountain of individual submissions is how well they reflect the original directive: “Emphasis should be divided between food and people.” It is this perspective that gives this work the feeling of a time capsule, a preserved glimpse of America in the early 1940s.

While I haven't yet read any others, I was intrigued enough to search our catalog to see what other books compiled from WPA sources we might have in our collection. This is what I found:

- Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover America by Scott Borchert - A literary history of the Federal Writers Project.

- American-made: the Enduring Legacy of the WPA : When FDR Put the Nation to Work by Nick Taylor - The WPA lasted for eight years, spent $11 billion, employed 8 and a half million men and women, and gave the country not only a renewed spirit but a fresh face. Its workers laid roads, erected dams, bridges, tunnels, and airports. They stocked rivers, made toys, sewed clothes, served millions of hot school lunches. When disasters struck, they were there by the thousands to rescue the stranded. And all across the country the WPA's arts programs performed concerts, staged plays, painted murals, delighted children with circuses, created invaluable guidebooks. We have only to look about us today to discover its lasting presence.

- Posters for the People: Art of the WPA by Ennis Carter - Posters for the People features nearly 500 of the best posters produced by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the 1930s and 1940s. As many of us will recall from high school history class, the WPA employed hundreds of out-of-work artists to raise awareness about public issues and civic life. Today these posters are celebrated as iconic works of graphic design; they also provide timeless messages about the merits of hard work, good parenting, a clean house, and personal hygiene.

- Kansas City 1940: A Watershed Year by John Simonson - Get a unique glimpse into Kansas City in 1940, a pivotal year in the city's history, preserved by a rescued archive of Work Project Administration photographs.

- The WPA Guide to 1930's Kansas - The WPA Guide, the first and only guidebook ever devoted to Kansas, was published in 1939. After six decades and more, its pages still provide a wealth of reliable historic, geographic, and cultural information on Kansas, as well as some intriguing lore that many modern-day readers will find new. Not the least of its contributions is the accurate picture it gives of Kansas between the Great Depression and World War II--of its industrial, agricultural, and natural resources.

- Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal by Marlene Park

- Posters of the WPA by Christopher DeNoon - Briefly describes the history of the WPA Federal Art Project, explains the silk screen process, and shows a variety of FPA posters promoting health, travel, the theater, and the war effort.

- The WPA Guide to New York City: The Federal Writers' Project Guide to 1930s New York - Originally published in 1939 at the time of the World's Fair, this is a reissue of this guide for time-travelers. It offers New York-lovers and 1930s-buffs a look at life as it was lived in the days when a trolley ride cost only a few cents, a room at the Plaza was $7.50, Dodger fans flocked to Ebbetts Field, and the new World's Fair was the talk of the town. The New York of 1939 was a city where adventures began under the clock at the Biltmore, the big liners sailed at midnight, and Times Square was considered the crossroads of the world.