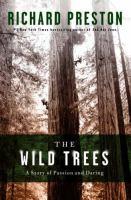

Richard Preston’s work of narrative nonfiction transported me to a place rarely seen by humans. Invisible from the ground, in the canopy of giant redwoods, exists a forest within a forest. Until recently the canopy was thought to be desert like, but thanks to the ecologists, botanists and naturalists depicted in Wild Trees, we now know, in the criss-crossed branches and burned out voids, the redwood nourishes many forms of life -- smaller trees and ferns grow in collected pockets of earth, a rainbow of lichen drip from the trunks and branches, and a particular type of salamander spends its entire life cycle in the canopy. Preston tracks the progress and evolution of redwood canopy research through the biographies of three key players. Ultimately, the author becomes part of the history himself.

Steve Sillet, well-known botanist and pioneer of giant tree canopy study, while still a college student, free climbed a 300-foot redwood. The abundance of life he found fascinated him and narrowed his focus of study. It would also ignite in him a passion and drive (bordering on obsession) that would eventually cost him his first marriage. Within the same week in 1987 as Sillet’s dangerous free climb, Michael Taylor was at the same national park on a guided tour. This sparked his obsession with tracking down the tallest living redwoods. Although he struggled to find direction in other areas of his life, Taylor was dedicated in his quest, spending most of his free time in the wilderness of the park. Several years later, the two teamed up, with Taylor hunting down the trees and Sillet climbing them. Their partnership would take them into challenging locations on the ground, high up in the canopies and in the space between the two.

Across the border in Canada, Marie Antoine grew up on a remote island of cliffs dotted with pines. She was comfortable with wilderness and taking risks—she could often be seen climbing tall pines and icy cliffs. A track scholarship brought her to the University of Oregon, where she first encountered old growth Douglas firs. She became interested in the lichen growing in their canopies and switched her major from nutrition to botany. Their shared interest in lichen would bring Antoine and Sillet together, first as research partners and then later as husband and wife. Together they perfected climbing practices and traveled the world studying old growth canopies. After receiving a grant, Sillet and Antoine embarked on a field study of Mountain Ash in Australia, enlisting the help of fellow tree climbing enthusiast and author, Richard Preston.

I feel a pull toward the natural world, but the realities of wilderness freak me out a bit, so I often experience a truly wild nature through the stories of others. A good author can take a reader out of their environment and transplant them into worlds real and imaginary. Preston does do this, eventually, but it takes some patience on the part of the reader. He approaches natural history through a narrative style, folding the science into the human histories. The transitions feel effortless and smooth, but the first part of the book involves many introductions. We are not only meeting Sillet, Taylor, Antoine and most of their friends, family, colleagues and researchers who came before them, but concurrently, we are learning about animal and plant species, the biology of the redwoods, and climbing terminology. Sticking with it pays off when, about halfway through, names and terms become familiar, freeing up enough mental space to allow you to wander around in the lush imagery. Overall, Wild Trees is engaging, exciting, and awe-inspiring.